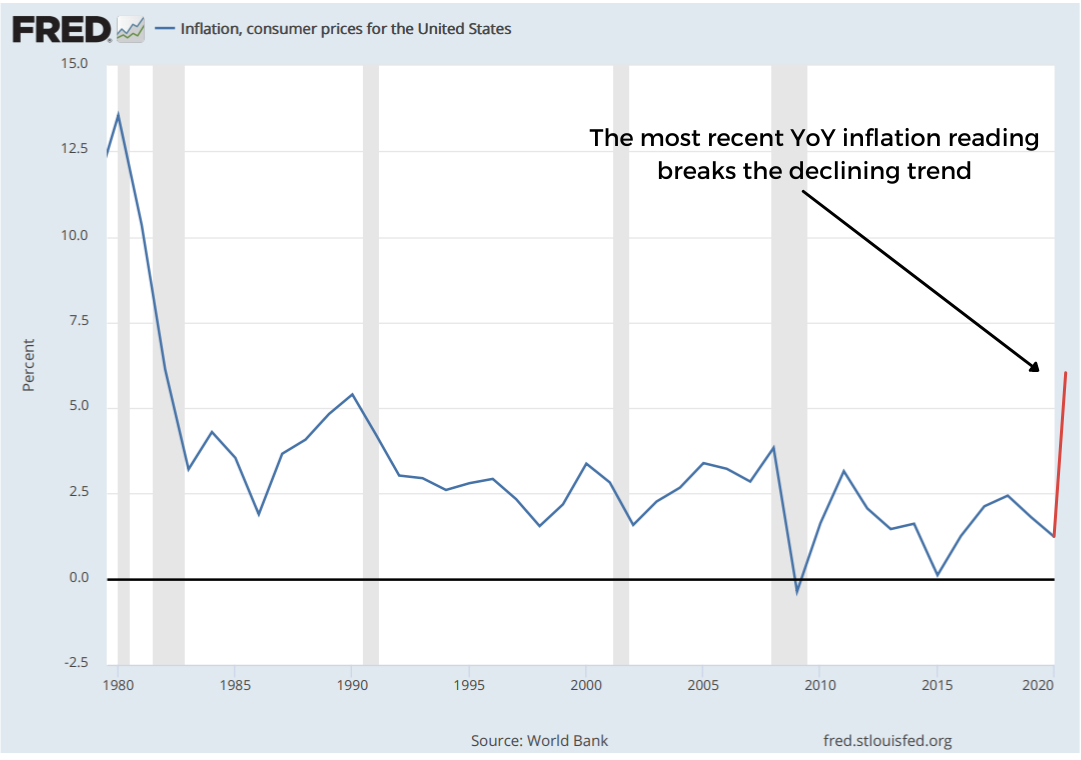

The fallout from COVID-19 may be reversing the long-term trend of low inflation, which has dominated the U.S. economy for decades.

Key Takeaways:

- The CPI surged almost 1% in June, the fastest rate in 13 years. Consumer prices have risen 5.4% over the last year.

- Two variables that have helped suppress inflation for decades might be reversing, which will create major problems for a financial system that runs on cheap money.

- As global markets face the risk of exorbitant public debt combined with rising interest rates, investors are starting to reconsider portfolio allocation strategies.

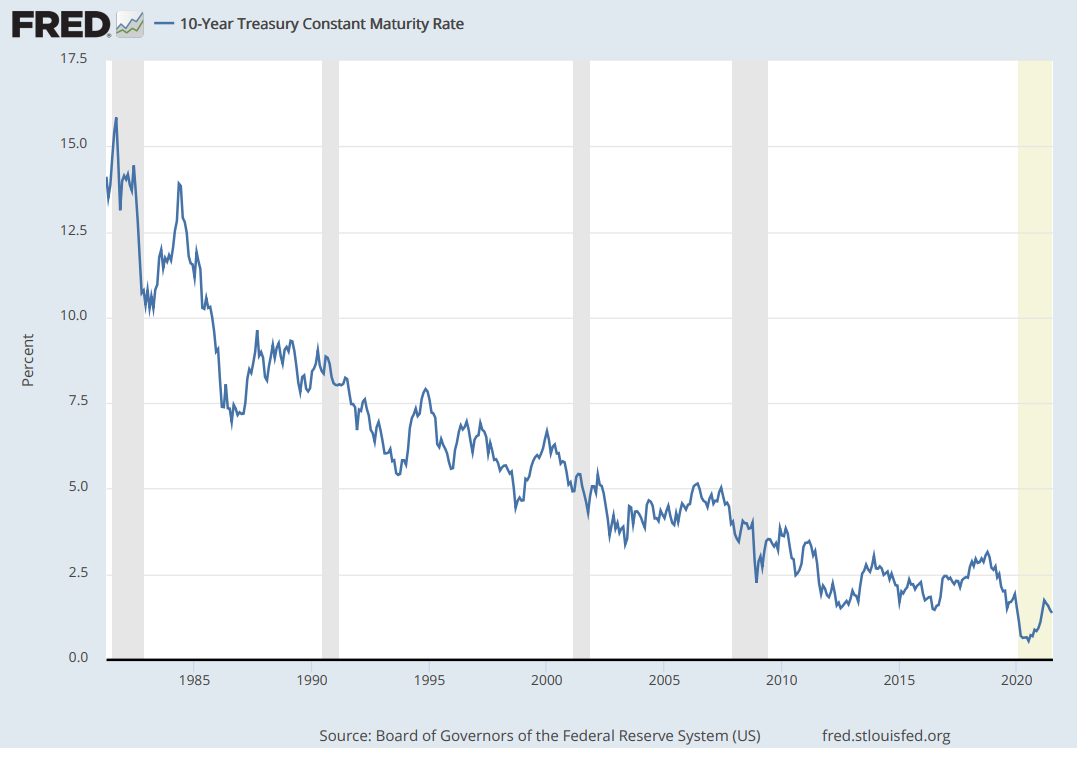

40 years of declining interest rates

The U.S. economy could be reaching the end of an era. The 10-year Treasury yield, which serves as a benchmark for interest rates in the United States, has been declining for the last 40 years (from 15.65% in 1981 to 1.37% now). This secular trend of declining rates and ever-cheaper money has encouraged extreme risk-taking – a strategy now engrained in almost every modern portfolio allocation.

Usually, you would expect a trend of declining interest rates to produce higher inflation. However, inflation has also been declining for the last 40 years. Why are they declining simultaneously?

The Wall Street Journal outlines two factors that have made this unusual 40-year correlation possible: globalization and demographics. Unfortunately, these trends appear to be reaching a secular turning point, which means they will no longer help in suppressing inflation.

- Globalization: As companies began operating on an international scale, they were able to lower costs by outsourcing labor to other countries (especially developing economies). Consumers enjoyed lower prices. Trade tension between the U.S. and China has already pushed prices higher in select markets, and the growing anti-globalization movement in the U.S. is signaling an end to ultra-cheap goods.

- Demographics: The United States and China have both enjoyed very large working populations over the last few decades. Working-age populations tend to produce more than they consume, which combats inflation. Today, the huge baby boomer generation has reached retirement age with tons of money in their pockets. China’s population is heavily skewed toward older generations, primarily because of the one-child policy in place from the 1980s until 2015. In the coming decades, supply could struggle to keep up with demand.

Rates cannot decline forever

At some point, the long-term patterns dominating the last 4 decades will shift, and investors will endure a period of painful returns as the market adjusts to entirely new rules. The Fed’s job is to lower interest rates when the economy hits a recession, and raise them when the economy runs too hot. When interest rates are near zero, the Fed has very few options in the case of a finanical crisis.

Could inflation be here to stay?

Despite these warning signs, the Federal Reserve continues to pedal the “inflation is transitory” narrative. In his semi-annual report to House lawmakers on Wednesday, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell acknowledged that inflation has proved to be a more serious problem than originally anticipated. He expects inflation to recede later this year, but also discussed his willingness to raise interest rates if necessary.

So, is he right to assume inflation will back off? Sure, some of the price pressures have come from temporary factors linked to COVID-19, such as broken supply chains and tightness in the labor market. But these factors alone do not explain why expert estimates have been so wrong lately.

Looking back at extreme inflationary episodes throughout history, we rarely see inflation naturally “stabilize” when it begins escalating. In fact, inflation almost always breeds more inflation. As prices begin to rise, investors and consumers raise their expectations for future price increases, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The government’s relationship with inflation

We tend to think that if inflation gets out of control, the government will step in and knock it back down with higher interest rates. Governments obviously have an incentive to protect their own currency, the nation’s economy, and financial markets from hyperinflation.

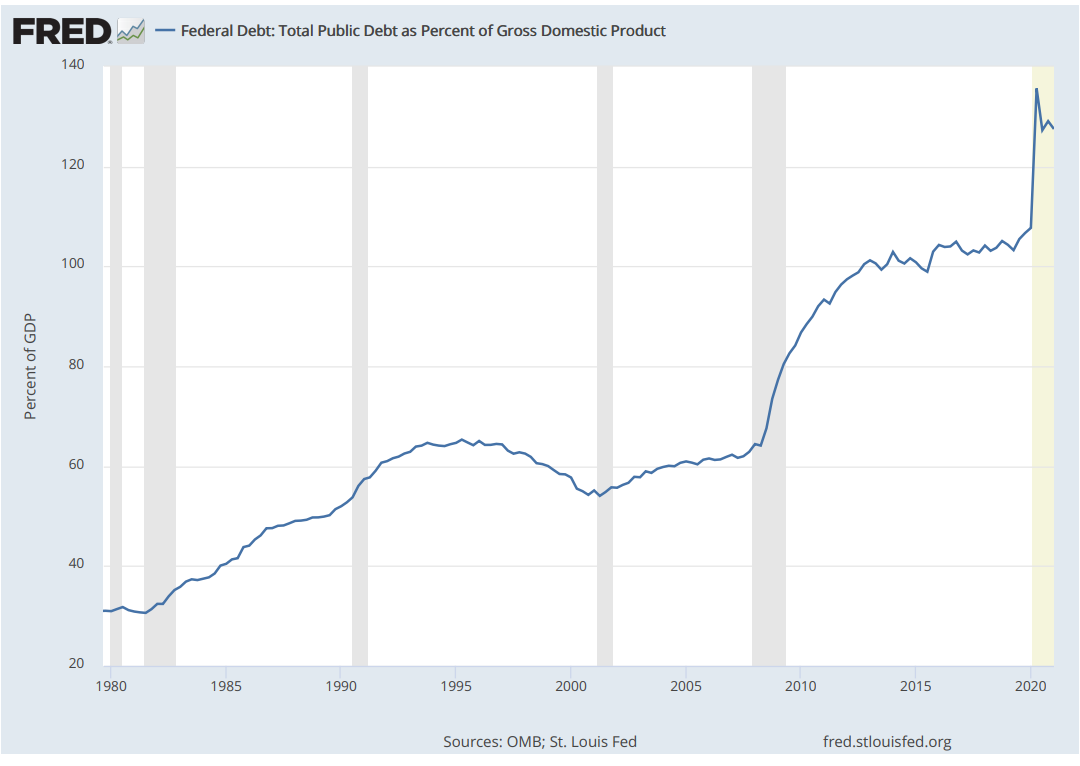

However, one major factor can alter the entire equation: debt. When governments rack up exorbitant amounts of public debt, they must pay interest on that debt. Creditors include individuals, businesses, pension funds, and other governments. The United States is projected to spend $300 billion on interest payments this year, almost 10% of federal revenue.

As interest rates rise, those interest payments start eating up more and more of the federal budget. During periods of rising rates, inflation can actually serve government interests by devaluing the currency and absorbing the debt. Public debt is measured in terms of that nation’s currency; $1 trillion is $1 trillion no matter how strong the currency is. So, if the dollar loses half its value compared to other currencies, suddenly that $1 trillion is much easier to pay off.

Public debt has exceeded GDP

So, is debt currently a concern for governments? Perhaps not…as long as interest rates stay low. After the extreme borrowing and spending to prop up the world economy during COVID-19, government debt reached 135% of GDP. Debt has reached its highest level since World War II.

Economists are unlikely to raise any warning flags because of a renewed philosophy on the nature of the debt. The latest doctrines to dominate mainstream economics, such as modern monetary theory, hold a much more favorable view of public debt than ever before. If these ideas are wrong, governments could be in for a rude awakening.

Inflation gets out of control, interest rates increase, and governments are suddenly saddled with exorbitant interest payments on their debt. They are left with a few options, all of them unfavorable: 1) raise taxes to pay for higher interest payments, 2) default on their debt, or 3) purposely let inflation devalue the nation’s currency to pay off all creditors.

The world economy is relying on a perilous combination of low inflation and low-interest rates. Change one of those variables, and everything topples over.

How should I react?

As the global financial system enters a new era, investors must reimagine the traditional 60/40 portfolio allocation. During the last four decades of declining interest rates, high-quality fixed income has provided an excellent buffer for equities. However, this trend is more the exception than the rule over all of U.S. market history, especially during times of higher inflation and higher real rates. We may be reaching a secular turning point in the stock-bond correlation.

Because of this, gold adds a strategic safe haven component to the traditional stock/bond portfolio. Not only does gold perpetually maintain purchasing power over time, but it also improves portfolio returns with less downside risk.

Secure gold savings, without the excessive fees.

Your weekly gold market commentary comes from our internal team of researchers and technical experts. Vaulted gives modern investors access to physical gold ownership at the best cost structure in the industry. With personal advising from industry experts and access to premier precious metals strategies, Vaulted is the key to life-long financial prosperity. Start protecting your portfolio today.

As always, thank you so much for reading – and happy investing!

Watch Golden Rule Radio for more of what’s in store for precious metals in 2021.