Money and the Fall of Rome

If ever there was an unbreakable civilization, the Romans held the title. Roman armies conquered 5 million square kilometers of territory and 20% of the earth’s population; Roman roads connected trade routes across Europe, Africa, and Asia; Roman art, literature, and philosophy layed the groundwork for modern Western culture.

And yet, Rome fell apart. Historians have debated the causes of Rome’s collapse for centuries, pointing to religious turmoil, erosion of traditional Roman values, incursions by Germanic tribes, and political corruption. However, at the heart of Rome’s decline lies a singular, pervasive factor: its monetary system.

Money touches every aspect of human life. Because of this, economic strength serves as the bedrock for cultural stability, technological innovation, and even artistic achievement. For centuries, Rome led the world in all these categories.

So, how did excessive government spending, currency devaluation, inflation, and a breakdown of trade end up tearing the empire apart? The answer can be found in Rome’s treacherous transition from hard money to easy money. Like many powerful civilizations before and since, Rome’s destruction came when its leaders resorted to currency debasement.

The Roman Currency System

The Romans built their monetary system on precious metals. The government minted and circulated the gold Aureus and silver Denarius to provide citizens with a reliable medium of exchange. A centralized currency also simplified tax collection.

The silver Denarius, first minted during the 2nd Punic War (218 – 201 BC), soon became Rome’s primary currency unit. The gold Aureus began circulating in the 1st century BC and gained popularity during the reign of Julius Caesar (46 – 44 BC). Both coins lasted until the reign of Constantine (306 – 337 AD).

Roman citizens also used other mediums of exchange, such copper and bronze coins and even land. However, the silver Denarius served as Rome’s economic backbone. Tracking the Denarius over its 500-year lifespan helps us understand how and why Rome collapsed.

Riches to Rags

During Rome’s expansion, tax revenue covered imperial expenditures. Some situations, such as war, infrastructure projects, or natural disasters pushed expenditures over revenue, but the Roman government always covered the difference with wealth produced from gold and silver mines or conquered enemies.

As the empire reached its zenith in 117 AD, Roman emperors encountered an ever-growing list of expenses without revenue to match. Rome’s massive military network perpetually added costs without ever reducing them. New borders needed protecting; new enemies needed fighting; new trade routes needed building. Eventually, the Romans ran out of ways to finance their expenditures, despite having such a large taxable population.

When a civilization runs out of money, they face three options:

- Take on debt

- Increase taxes

- Debase the currency

Option 1: Taking on debt pushes the problem of financial default into the future. As you might imagine, governments have a terrible track record of paying off debt once they acquire it. Rome did not have the option of selling bonds like modern governments, so emperors rarely took on debt.

Option 2: Rulers that want to keep their heads tend to avoid burdening their populations with excessive taxation, especially when they can choose a much less obvious and more sinister option 3. Only in Rome’s final years did emperors resort to debilitating taxation.

Option 3: Debasing the currency means reducing the value of each currency unit. This allows the government to pay off the same nominal expenditures with a less valuable currency. Of course, it also causes the prices of goods and services to rise.

The Denarius: A Brief History

After its inception during the 2nd Punic War, the silver Denarius maintained a consistent weight and purity for nearly 300 years. Caesar Augustus, Julius Caesar, and other great Roman leaders of that era were known for their commitment to a stable monetary system.

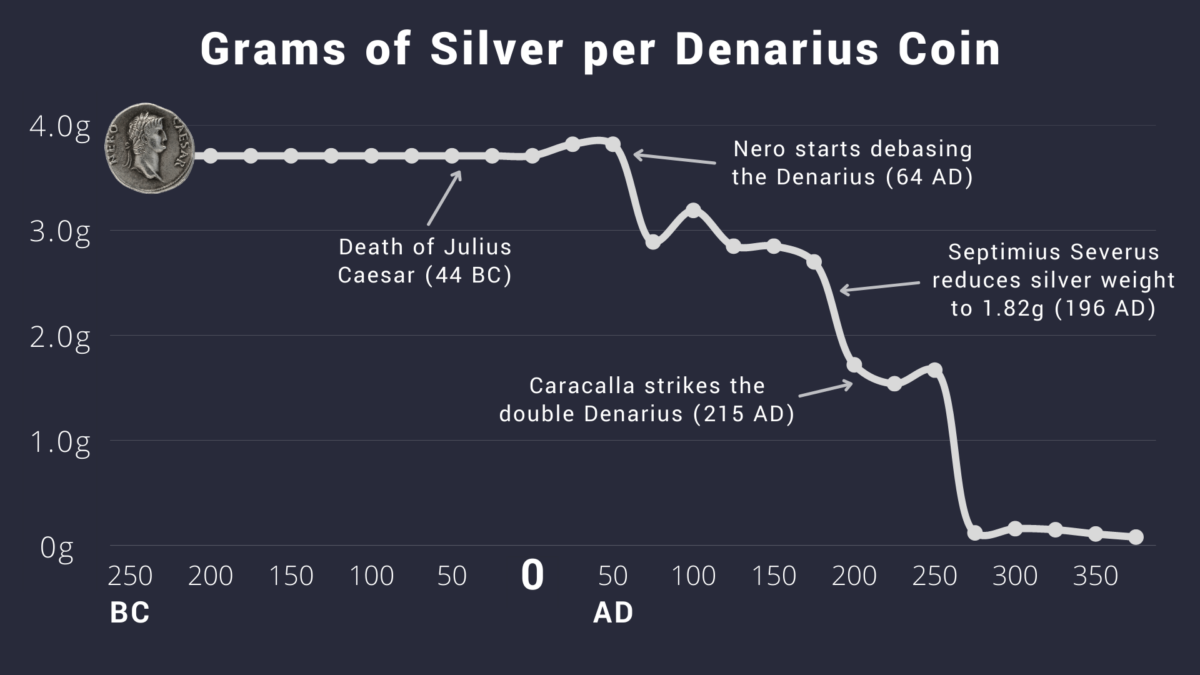

In 54 AD, Emperor Nero took power. Conflicts across the empire drained Rome’s coffers during this period, including the Roman–Parthian War, the Great Jewish Revolt, and several civil wars. In July of 64 AD, the Great Fire of Rome destroyed two-thirds of the city. To cover his extravagant spending, Emperor Nero instituted the first round of Denarius debasement. Historians estimate Nero reduced the coin’s silver content by 20%.

The Roman Empire reached peak territory in 117 AD under Emperor Trajan. In 122 AD, Emperor Hadrian started building Hadrian’s Wall. In 126 AD, Marcus Agrippa commissioned the Pantheon. These projects, along with constant pay raises for Roman soldiers, multiplied Rome’s financial burden. Trajan, Antoninus Pius, Lucius Verus, Commodus, and Septimius Severus all devalued the Denarius, gradually extracting wealth from the public to cover expenses.

Some emperors, such as the great Marcus Aurelius, worked to preserve the integrity of the denarius despite Rome’s economic challenges.

All Roads Lead to Inflation

In the late second century, a series of disasters aggravated Rome’s economic problems. The Antonine plague of 165 AD killed anywhere from 5 to 20 percent of Roman citizens. Germanic tribes began invading territories along the northern border, forcing Rome to increase military spending.

To solidify his power, Septimius Severus (193 – 211) mimicked the actions of destitute leaders before him. By reducing the amount of silver in each Denarius, Severus was able to drastically increase soldier pay. In the first 35 years of the 3rd century, soldiers’ wages tripled. He also built extensive social welfare programs, including free distributions of grain and olive oil, and free healthcare through state-sponsored hospitals and clinics.

Severus’ oldest son, Emperor Caracalla, took a different approach. In 215, he introduced a new coin: the Antoninianus or “Double Denarius.” The Double Denarius was supposed to be valued at two Denarii, but only contained about 1.5 times the silver.

End of Money, End of Society

The emperors minted millions of coins to cover expenditures, flooding the economy with worthless pieces of copper alloy with a thin layer of silver. This destroyed public confidence in Roman currency, and rampant inflation took hold. Gold and silver mines ran out, as did Rome’s supply of conquerable enemies.

The Imperial Crisis, from 235 to 284, saw over 20 emperors rise and fall. This rivals the number of leaders Rome had in the preceding 250 years. By the mid third century, the Denarius had lost nearly all its intrinsic value. Inflation had sucked the wealth out of 99% of society and concentrated it in the hands of a few elites.

Unsurprisingly, this led to mob riots and civil wars. In 293 AD, Emperor Diocletian attempted to restore peace and economic stability through price controls (Edictum de pretiis rerum venalium), regulations, and other administrative reforms. He also instituted the Tetrarchy, which split Rome into four parts.

Many Romans fell into poverty under increasingly debilitating taxes throughout the 4th century. In fact, some citizens sold themselves as slaves to larger landowners to avoid taxes. Unfortunately, inflation and civil unrest were so deeply rooted that eliminating them meant eliminating Rome itself. Eventually, barbarian invasions delivered the final blow.

The Gold Standard

During his reign in the early 4th century, Constantine the Great began the process of building a new empire. In 312 AD, he introduced the gold Solidus coin in an effort to reestablish trust in Roman currency.

The Solidus, a pure gold coin weighing 4.5 grams, provided a new monetary backbone in Europe. A sound monetary system, which the Romans had abandoned, helped Constantine lay the foundation for the world’s next great power: The Byzantine Empire.

To illustrate the Denarius’ debasement against a gold standard: during Julius Caesar’s time, the gold Aureus was worth 25 Denarii. Three hundred years later, one Aureus was worth thousands of Denarii. By 330, one gold Solidus coin was worth hundreds of thousands of Denarii. By the end of the Roman Empire, one Solidus could purchase millions of Denarii.

Currency Debasement Today

Because Roman elites could not print an unlimited number of gold and silver coins, they had to employ some sneaky tactics when overspending. In modern economies, central banks have a much easier time debasing their currency.

Modern governments perpetually spend more than they earn, just like the emperors of old. They get away with it because, just like in the Roman Empire, inflation is not directly connected to currency debasement. If the emporer debased the currency by 50%, it might have taken a decade for the price structure to adjust. The same is true today. By the time the economy bears the full cost, the instigating politicians are long gone.

This leaves the problem at the feet of new politicians, who must debase the currency further to pay the debts of their predecessors. Since the Federal Reserve’s creation in 1913, the U.S. dollar has lost more than 98% of its purchasing power. Hyperinflationary episodes, such as those in the early Soviet Union, Germany after WWI, and Zimbabwe in 2007, usually stem from a combination of excessive money printing and other political factors such as war and corruption.

History remembers favorably those Roman Emperors who instituted a hard money system, such as Augustus, Julius Caesar, and Constantine. On the other side of history are those who destroyed the currency, such as Nero and Caracalla.

By eliminating any trace of scarcity, Rome converted the world’s most trusted and stable currency into millions of worthless lumps of tarnished metal. Money is the builder and destroyer of human civilization, which is why the discipline of economics is so vitally important.

Rome was not the first or last to sow the seeds of economic decay with a transition from hard money to easy money. Someday, history will look back on our current leaders like we look back on the emperors. Let’s hope we do not make the same mistake.