In just a few years, France transitioned from a hard-money system backed by gold and silver to an easy-money regime built on paper promises. The result was a classic boom-and-bust cycle whose lessons still echo today.

John Law to the Rescue

Let’s travel back to 18th century France. When King Louis XIV died in 1715, he left the French economy in shambles. His reckless spending on the Palace of Versailles and the Franco-Dutch War had drained state coffers, forcing the monarchy to take on exorbitant debt.

He left a legacy of high taxes and a sluggish economy. France needed help, and they found it in a Scottish economist (and gambler) named John Law.

The only thing crazier than John Law’s economic theories is his backstory. In his early 20’s, he killed a fellow young man in a duel. The judge in London condemned him to be hanged, but his friends helped him escape prison before the sentence could be carried out. He fled England and spent years traveling and studying the monetary systems of Europe.

Law was known for his brilliant mathematical mind…and propensity for all manners of debauchery. When French royalty called for his assistance, he introduced a revolutionary idea: paper currency.

The Move to Easy Money

Prior to Law’s influence, France functioned on a hard money system backed by gold and silver. This made it very difficult to increase the money supply.

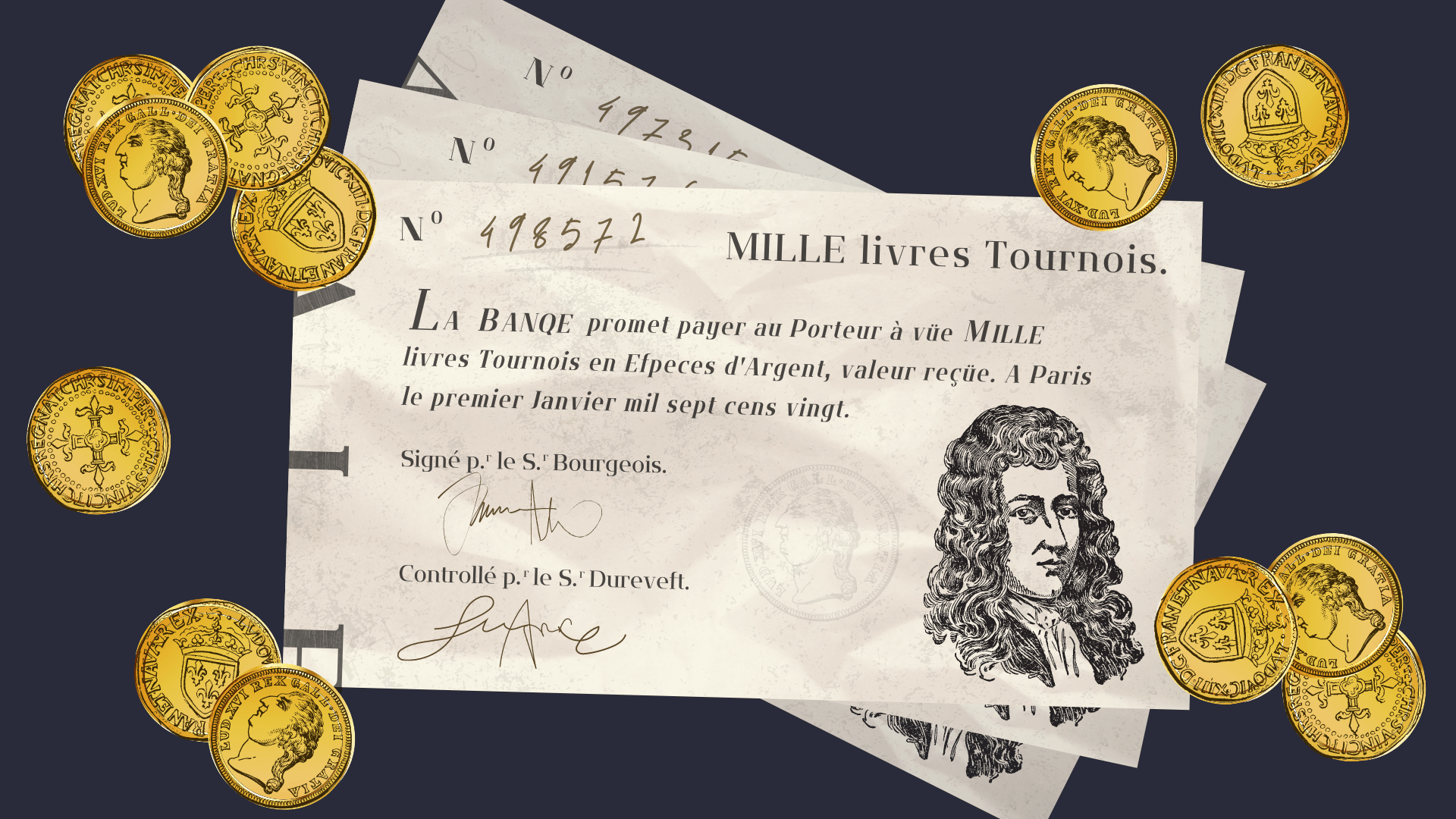

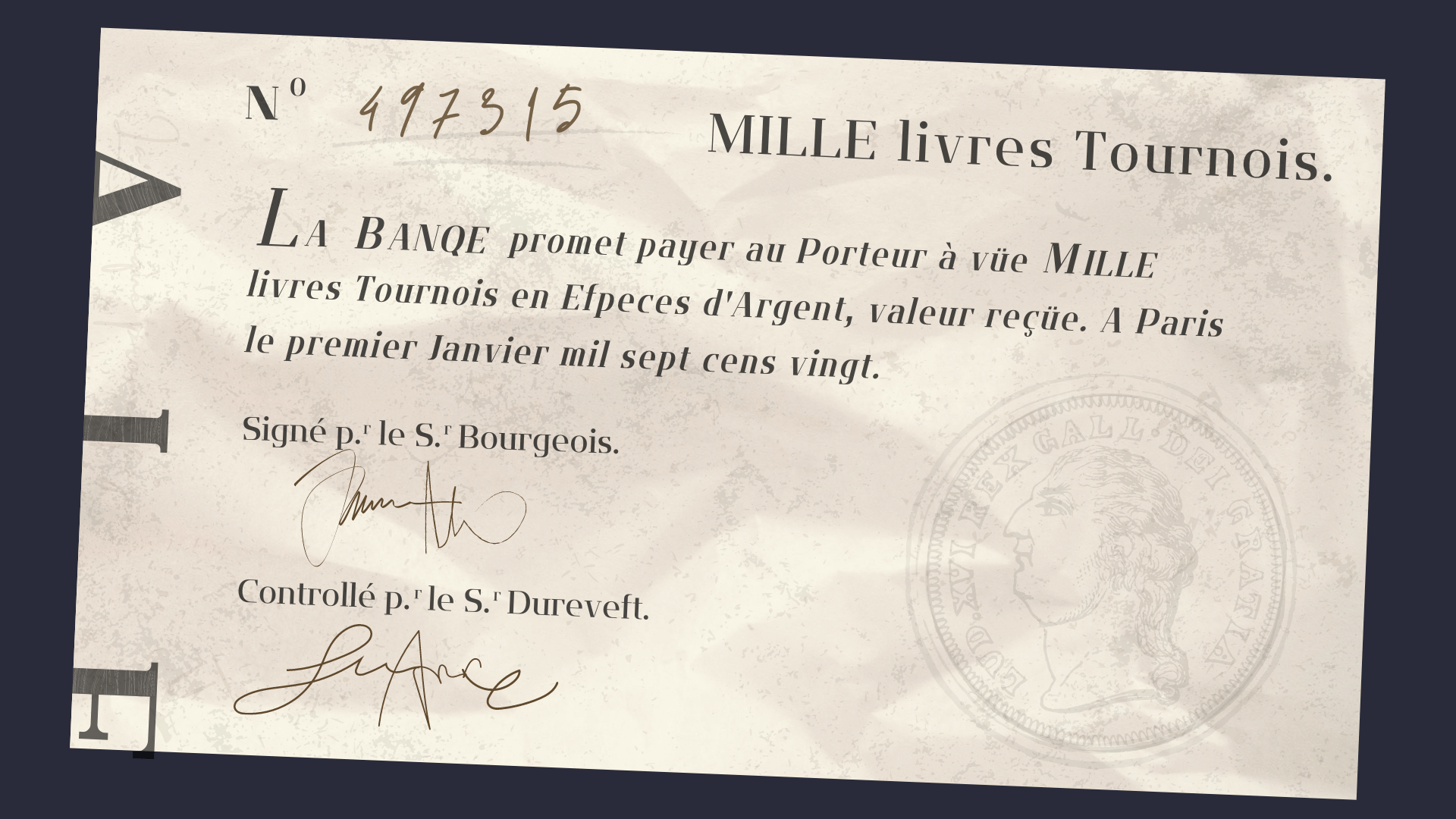

In 1716, Law founded the Banque Générale, a private bank that issued paper notes redeemable in gold and silver. These notes circulated more easily than coins and were initially welcomed. Trade picked up. Confidence rose.

However, as demand for paper currency grew, the bank couldn’t resist the urge to keep printing and distributing banknotes. Soon, there was not enough metal reserves to back the paper. John Law knew these notes needed some sort of backing, and saw an opportunity in the New World.

The Mississippi Craze

In August 1717, Law acquired the Mississippi Company, which managed trade between the mainland and France’s colony along the Mississippi River. This colony stretched from modern-day Louisiana all the way up to Canada. The company transported settlers and slaves, appointed government officials, and managed trade in the territory.

To fund his operations, Law started selling shares of the company. Investors lined up to finance the enterprise as rumors spread of silver and gold in the Mississippi territory.

In December 1718, Law’s bank was nationalized and renamed Banque Royale or “Royal Bank”. In the summer of 1719, the Mississippi Company acquired a large portion of France’s national debt, giving Law absolute authority over France’s monetary system. His banknotes no longer had to be denominated in gold, which allowed him to print money to his heart’s content.

Whenever the growing Mississippi Company needed capital, Law simply issued more banknotes.

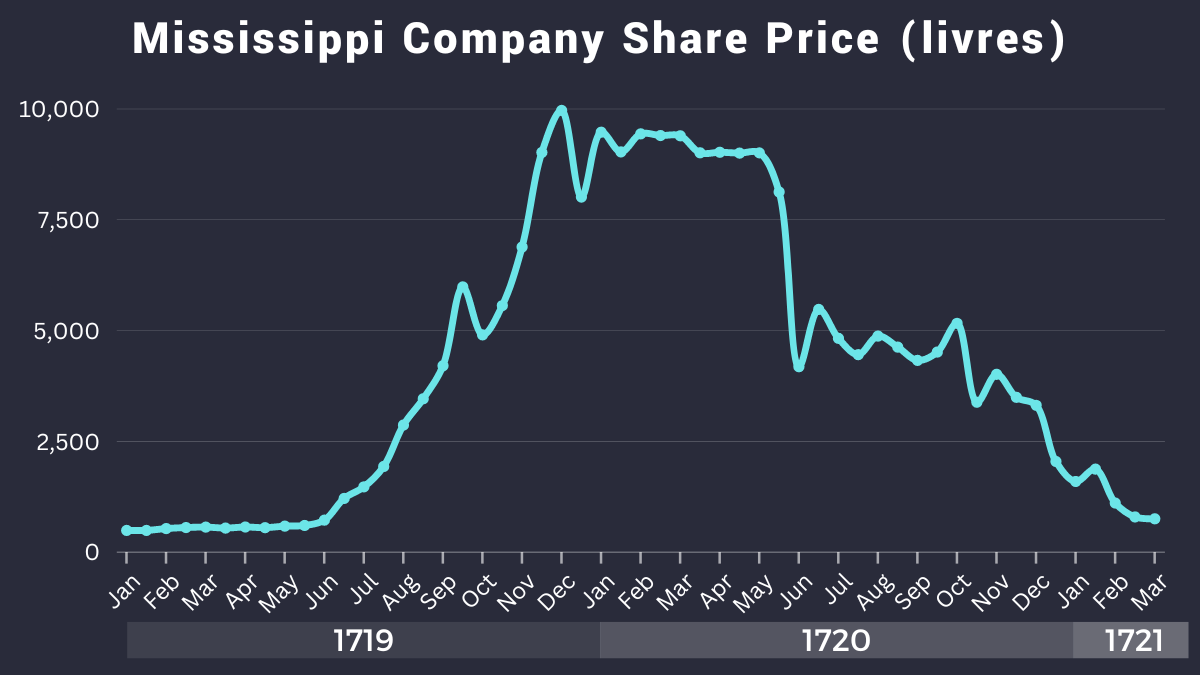

Mississippi Company share value skyrocketed. In 1719 alone, the share price rose almost 2,000% (hardly a surprise, considering the company had access to unlimited money). The Mississippi Company created millionaires left and right as more and more investors clamored for a piece of the pie. Even French servants were sucked into the craze, investing everything they had into the company.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago

Boom and Bust

In January 1720, everything changed. Investors started cashing in their gains and the share price stalled. Investor sentiment shifted and everyone started trading their paper money back to gold. But there was a problem: Law’s bank had printed 5 times the amount of paper money than it had in gold reserves.

John Law saw the writing on the wall. In an effort to stop the transition back to hard money, he banned the possession of precious metals. He justified this decision by railing against the ‘hoarding of money’ – the same language the U.S. government used when they banned the possession of gold in 1933. In both instances, citizens were forced to pay taxes and settle debts with paper money.

Inflation took hold as the French currency withered away. Food prices doubled. By September 1721, the share price had dropped to 500 livres (down from 10,000 livres just two years prior).

The Aftermath

John Law’s genius quickly turned into his worst nightmare. His scheme turned peasants into millionaires and back to peasants in a matter of months. He fled Paris soon after the collapse, leaving his family and wealth behind. Law died a poor man in Venice in 1729.

France soon switched back to a gold-backed currency system, which helped stabilize the economy. However, citizens held onto their frustration with French royalty, eventually culminating in the French Revolution in 1789.

A Mirror to Modern Money

The Mississippi Bubble is just one example of the easy money trap, to which countless nations have fallen victim. And yet, John Law’s ideas live on in modern economic thought. Pick up any textbook on macroeconomics and you’ll see all sorts of mathematical justifications for Law’s money-printing mania.

Perhaps most frightening is the fact that the Royal Bank’s operations are nearly identical to the strategies of the U.S. Federal Reserve. Here are some policies that the two central banks share:

- Buying government bonds to stimulate the economy (the Fed purchased $4.4 trillion worth of treasuries and mortgage-backed securities in the two years following the COVID-19 recession)

- Generating market rallies with newly printed currency (since the Global Financial Crisis, stock market performance has been highly correlated with new money creation)

- Stoking demand for speculative assets (the Fed artificially lowers interest rates, pushing investors toward riskier asset classes)

Warning Signs

The transition from hard money to easy money is not a new experiment. Does this mean the United States is doomed to the same fate as 18th century Frace?

Certainly not – as long as the U.S. maintains a certain level of “hardness” in the U.S. dollar. Unfortunately, the Global Financial Crisis triggered a strong move away from sound monetary policy. Since 2008, the Fed has engaged in unprecedented levels of accommodative monetary policy through quantitative easing and near-zero interest rates.

Warning signs are flashing: extreme speculation in the stock market, unsustainable government debt, rising inflation (to name a few). Luckily, modern investors are in a better position than investors in 18th century France. They have tools to prepare for any sort of bust central bankers might trigger during their relentless pursuit of the boom.

We hope Vaulted can serve as one of these tools. Vaulted allows you to create your own gold standard by acquiring physical gold at the best cost structure in the industry. We handle storage and insurance – all you need to do is sit back and watch your investment grow.