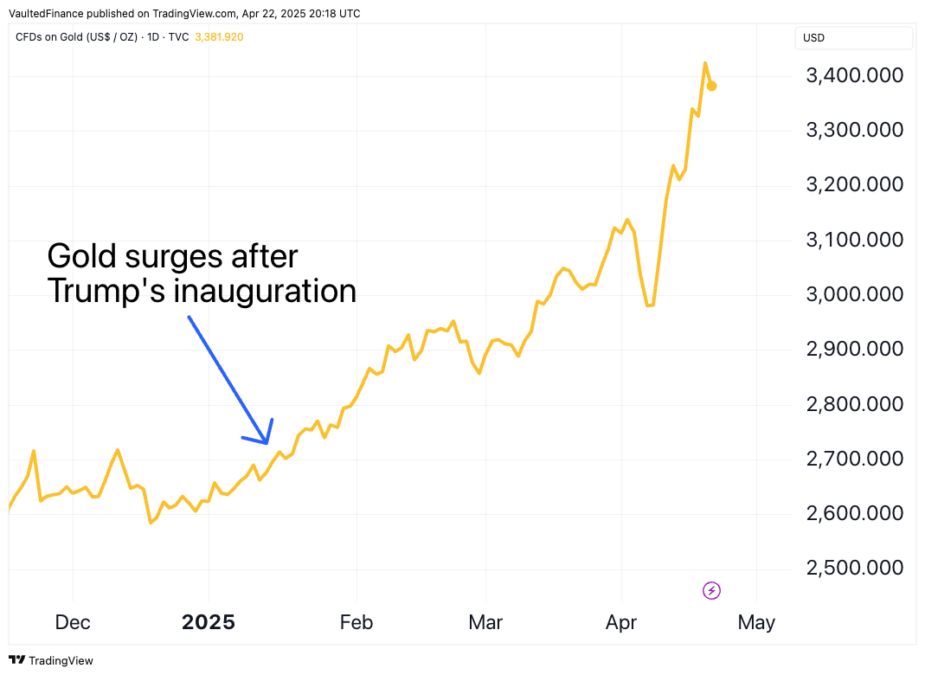

Trump’s tariffs have sent gold to an all-time high. Markets expect tariffs to cause some combination of higher inflation, a declining U.S. dollar, geopolitical tensions, and more foreign gold demand.

What is a tariff?

A tariff is a tax imposed by a government on goods imported from other countries. If a company wants to manufacture a good in a foreign country and sell it in the United States, it must pay a tax to the U.S. government.

In practice, tariffs make foreign goods more expensive than domestic goods. So, are tariffs good or bad?

The downsides of tariffs

Economists since the great Adam Smith have known that free trade and specialization leads to higher overall productivity. The free market makes it profitable to produce goods in countries where they can be produced most efficiently and freely flow where they are valued the most. Tariffs place artificial barriers that impair these benefits.

In a tariff-protected industry, resources (labor, capital, and materials) are diverted away from potentially more productive uses. Production becomes inefficient – more input, less output. Consumers end up paying more for goods, whether domestically produced (because of reduced foreign competition) or imported (because of tariffs).

Additionally, tariffs can spark retaliatory trade wars. When nations are economically tied through trade, they are less likely to enter into military conflict. We should remember the old adage: Nations either trade goods or they trade bullets.

The benefits of tariffs

Given these downsides, why do governments impose tariffs?

Typically, two reasons: 1) protect domestic industry, and 2) generate government revenue.

1. Protecting domestic industry

By raising the cost of foreign imports, tariffs protect industries that produce goods domestically. This can protect local jobs and encourage consumers and businesses to “buy local.”

Using tariffs to shield manufacturers from cheap foreign competition was the norm for most of U.S. history. However, as national economies became more dependent on each other, the U.S. shifted away from protectionism.

After World War II, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1947 promoted tariff reductions. Agreements such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA, 1994) and the establishment of the World Trade Organization (WTO, 1995) further encouraged free trade.

The Trump administration has been highly focused on this issue. For decades, American companies have gradually moved their manufacturing overseas (known as offshoring) to take advantage of lower labor costs, less regulation, and cheaper raw materials. Apple relies heavily on manufacturing partners in China for iPhone assembly. General Motors builds many car parts in Mexico. Nike and Gap have concentrated clothing production in Southeast Asia.

Offshoring has resulted in more efficient production, but at a high cost to Americans whose jobs were moved overseas. The once great steel mills and auto plants across the Rust Belt (Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, Indiana) are now shut down. North and South Carolina’s textile and apparel industry has been gradually moving overseas since the 1970’s.

The Trump administration has a stated goal of using tariffs to incentivize U.S. companies to bring manufacturing back home.

This could (theoretically) have other benefits as well. COVID-19 and the Russia-Ukraine war demonstrated that our international supply chains are vulnerable to geopolitical disruptions. Is it possible to create more stable and resilient supply chains if they are concentrated in the United States?

There may be some legitimate concerns about relying too heavily on foreign nations for certain goods and materials. Certain sectors (steel, energy, telecommunications) are deemed critical for national defense and basic infrastructure. Tariffs on relevant imports may be justified to ensure the country is not overly reliant on a foreign supplier during a geopolitical crisis.

2. Generating government revenue

For the first 120 years of U.S history, the U.S. government funded itself primarily through tariffs.

The Tariff Act of 1789 was the first significant piece of legislation passed by the newly formed Congress, signed into law by President George Washington. Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, the U.S. government levied tariffs on iron, steel, textiles, glass, sugar, tobacco, coffee, tea, coal, and other goods.

The 16th Amendment, ratified in 1913, gave Congress the power to the tax income. Corporate and personal income taxes quickly became the primary sources of government revenue.

The Trump administration has revived tariffs as a source of government revenue. By combining higher tariffs with lower domestic corporate taxes, the goal is to create a more business-friendly environment and make it easier for companies to invest in new factories, equipment, and workforce expansion in the United States. Whether these trade-offs will actually result in a stronger U.S. economy and generate sufficient government revenue remains uncertain.

How will tariffs impact gold?

Historically, tariffs have been positive for the gold market.

Gold prices are primarily driven by the following factors:

- Inflation expectations (Higher inflation expectations = higher gold prices)

- Interest rates (Higher interest rates = lower gold prices)

- Strength of the U.S. dollar (Stronger U.S. dollar = lower gold prices)

- Central bank gold demand (Higher demand from central banks = higher gold prices)

- Geopolitical stability (Less stability = higher gold prices)

We will look at how tariffs influence each of these factors and, in turn, how they tend to impact the gold market.

Tariffs vs. inflation expectations

Tariffs add an additional cost to imported goods and raw materials. These costs must ultimately be passed onto consumers. As a result, tariffs fuel inflationary pressures.

Gold has always been an inflation hedge because of its strictly limited supply and a very strong base of demand. As inflation expectations climb, gold becomes more attractive because investors use it to protect against the eroding purchasing power of their currency.

Tariffs vs. interest rates

As a rule, gold is inversely correlated with interest rates. Gold is a non-yielding asset. All other things being equal, investors prefer to earn a yield. When interest rates rise, gold demand falls. When interest rates fall, gold demand rises.

So how do tariffs impact interest rates?

Perhaps Trump’s tariffs will attract foreign investment into U.S. production (or prevent domestic companies from investing their capital overseas). If so, capital in the U.S. will become more abundant, pushing interest rates down. However, tariffs may also restrict global trade and cause investment capital to dry up, making borrowing more competitive and pushing interest rates higher.

We also need to consider the Fed. If tariffs increase inflation, the Federal Reserve may respond by raising interest rates. However, if the tariffs slow economic growth, the Fed may lower interest rates to encourage borrowing and stimulate economic activity.

We should emphasize that real interest rates matter more for the gold market than nominal interest rates. Real interest rates are nominal interest rates minus inflation. Because tariffs generally push inflation higher (other things being equal), they tend to drive real interest rates down.

Tariffs vs. the U.S. dollar

The dollar and gold tend to be inversely correlated. When the dollar weakens against other currencies, gold prices tend to rise, and vice versa.

How do tariffs affect the strength of the U.S. dollar?

The strength of a currency is determined by supply and demand. When people acquire more dollars, the currency strengthens against other fiat currencies (Euro, yen, franc, pound). People acquire dollars for three main reasons:

- To buy dollar-denominated assets (Treasuries, U.S. stocks)

- To buy goods and services from the United States (oil, wheat, tech)

- To buy global commodities priced in USD (oil, gold)

If investors believe tariffs will harm the U.S. economy (due to inflation, lower growth, and trade wars), they will invest their money elsewhere. This will reduce capital flows to U.S. assets, decreasing demand for the dollar and weakening it against foreign currencies.

However, if investors believe tariffs will benefit the U.S. economy, they will acquire more dollars to buy U.S. assets. The U.S. may be more resilient than other nations in the face of retaliatory trade wars.

Many nations (especially BRICS) are working to “de-dollarize” their economies. If the U.S. dollar does continue to play a smaller role in international trade, gold could emerge as an alternative. It is already a neutral, universally accepted store of value, and no other national currency is considered stable or transparent enough to serve the role that the dollar currently serves.

Tariffs vs. central bank gold demand

Even though national currencies no longer operate on the gold standard, central banks all over the world still own huge reserves of physical gold (about 37,000 metric tons in total, which accounts for nearly 20% of all gold ever mined). Gold’s low correlation with other assets reduces portfolio risk, while its universal acceptance makes international transactions easy.

When tariffs escalate trade disputes, central banks—especially in emerging markets—get nervous about relying too heavily on foreign currencies. In response, they tend to boost their gold reserves, treating gold as a safer, more neutral asset. Tariffs tend to make gold more attractive for central banks, driving up demand and supporting higher gold prices.

According to the World Gold Council, central banks have been net buyers of gold for the last 15 consecutive years. Gold demand has risen sharply as tariffs and protectionist policies have become more mainstream.

Tariffs vs. geopolitical stability

Tariffs are typically seen as bad for geopolitical stability. Two countries who freely trade with each other end up economically co-dependent, which creates strong disincentives for military conflict (war ends up hurting your economy just as much as theirs). Tariffs remove some of these disincentives.

Gold is a safe-haven asset. When other assets decline, gold tends to perform well. As a result, geopolitical instability generally increases gold demand.

Lessons from History: The Impact of Tariffs on Gold

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff (1930)

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff provides a stark example of the relationship between tariffs and gold.

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 was the most infamous tariff policy in U.S. history. Designed to protect American farmers and manufacturers during the early stages of the Great Depression, it raised tariffs on thousands of imported goods. However, instead of stimulating the economy, it triggered retaliatory tariffs and collapsed global trade.

At the time, the dollar was on the gold standard (which means every dollar was backed by an exact amount of physical gold). As the crisis worsened, individuals and businesses realized that banks did not have enough gold to cover the dollars in circulation, which means their dollars were worth nothing. People rushed to exchange their dollars for physical gold at their bank. Since no one had enough gold to cover the outstanding dollars, banks began failing.

On Monday, your life savings were deposited at a bank. On Tuesday, the bank was gone, along with your savings.

In 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt confiscated gold from citizens and made private gold ownership illegal. He then increased the official price of gold from $20.67 to $35 per ounce. This devalued the dollar by 41% and allowed the government to greatly increase the money supply.

The Trump Tariffs (2018 – present)

In 2018, President Donald Trump initiated tariffs targeting Chinese imports. This move escalated into a trade war, with both the U.S. and China imposing multiple rounds of tariffs on each other’s goods. Gold prices rose from $1,200/oz to $1,500/oz in the following year. COVID-19 followed shortly after, during which gold peaked at $2,070/oz.

In the first few weeks of Trump’s second term, he introduced an even more aggressive tariff strategy. In response, gold rocketed to an all-time high.

Vaulted: buy gold with the tap of a finger

Vaulted is the simplest way to own physical gold. It takes 30 seconds to set up your free Vaulted account, where you can buy real gold and silver in any quantity.

You have direct ownership of segregated, serial-numbered bars, which you can take delivery of at any time.