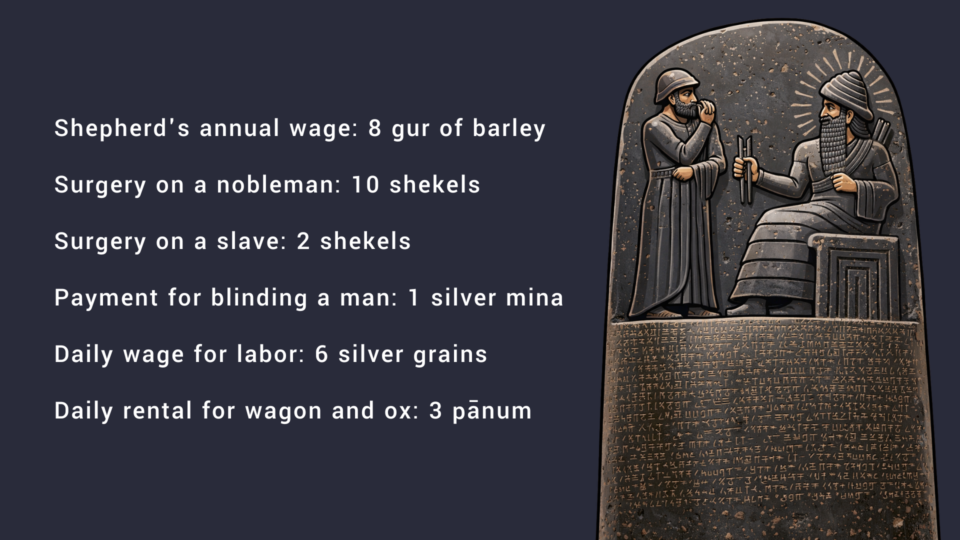

This article uses gold as a stable benchmark to translate wages and prices from Hammurabi’s Code into modern terms.

Comparing Prices Across 3,770 Years

How do we compare the price of food, surgery, or a day’s labor from 1750 BC to the present? The value of money is not constant. Currencies come and go, purchasing power changes, and inflation distorts value over time.

The two buckets of barley that constituted a day’s wage in ancient Babylon would be nearly worthless today if taken at face value. To bridge this gap, historians and economists must find a common reference point that remains relatively stable across eras.

Gold as a Historical Yardstick

One useful approach is to use gold as a “common denominator.”

Since gold has served as the world’s most stable and enduring store of value across nearly all major civilizations, it serves as a reliable benchmark for comparing the value of goods, services, and labor across history.

Here is conversion procedure we’ll use:

- Start with the price in ancient terms (e.g. 5 shekels of silver, 8 gur of barley).

- Convert that price to an equivalent weight of gold using historical exchange rates.

- Convert the gold weight to today’s money by using a current gold price (we use $4,500 per troy ounce).

The Babylonian Monetary System

In the ancient city of Babylon of Hammurabi’s time (1750 BC), silver and barley (a type of grain) both served as money. Coins did not exist. Payments were made by weight or volume.

Exchange Rates

The silver–barley exchange rate was fixed by law and remained stable for centuries: 1 silver shekel = 1 gur of barley. (Source)

One shekel of silver is equal to ~8.4 grams (by weight). One gur of barley is equal to ~300 liters (by volume).

For reference, 8.4 g of silver is about 0.27 troy ounces. At the fixed barley rate, 1 troy ounce of silver could buy nearly four gur of barley (1,200 liters) – enough grain to feed an average person for a year or more. Precious metals were scarce relative to staple goods, so a tiny weight of silver could buy large quantities of grain.

During Hammurabi’s reign, the silver:gold ratio was about 6:1 (6 oz of silver = 1 oz of gold in value).

This 6:1 ratio is much lower than the 15:1 ratio common in later antiquity (meaning silver was more highly valued in early Mesopotamia).

| Currency (weight) | Exchange Rate |

|---|---|

| Silver shekel | 1 shekel = 180 grains of silver |

| Gram of silver | 8.4 grams = 1 shekel |

| Gram of gold | 6 grams of silver = 1 gram of gold (in value) |

| Troy oz of gold | 31.1035 grams = 1 troy oz |

| U.S. dollars ($) | $4,500 = 1 troy oz |

| Currency (volume) | Exchange Rate |

|---|---|

| Gur of barley | 1 shekel = 1 gur (in value) |

| Liter of barley | 300 liters = 1 gur |

Ancient Babylonian Prices and Wages (vs. Modern)

Hammurabi’s Code sets specific prices in grain or silver. We have converted each price into today’s U.S. dollars using the current gold price and historic exchange rates between grain, silver, and gold.

Medical Fees

- Law §215: If a physician performs surgery on a nobleman (such as saving his eye or treating a serious wound), he receives ten shekels of silver, equivalent to $2,025 in today’s money.

- Law §216: The same procedure performed on a commoner is priced at five shekels, equal to $1,013. This fee was enormous, considering common laborers only earned $1,200-1,600 annually in subsistence wages.

- Law §217: The same procedure on a slave earns two shekels, equal to $405. Slaves themselves would not pay (they had no personal wealth); it was the slaveowner who compensated the doctor as reimbursement for restoring their “property.”

- Law §221: If a physician repairs a broken bone or heals a sore tendon, he will be paid five shekels of silver, or $1,013 in today’s money.

- Law §198: If you blind a commoner or break their bone, you owe them one mina of silver (60 shekels), equal to $12,153. This represents 8–10 years of a field laborer’s wages, a massive penalty by Babylonian standards.

The disparity in fees (10 vs 5 vs 2 shekels) illustrates class differences in Babylon. The life of a nobleman was literally valued higher in law than that of a commoner or slave.

The high cost of medical services relative to average wages suggests that trained physicians were in short supply.

Hammurabi’s Code also stipulates harsh penalties for failure: if the surgeon botched the surgery and caused death or blindness, there were brutal punishments (like cutting off the surgeon’s hand, §218).

Builders’ Wages

- Law §228: A house builder is paid two shekels of silver for each mūšarum of area (equal to about 390 sq ft). This equates to $405. A typical house would have been 2-3 mūšarum, so a builder was paid 4-6 shekels per completed house.

This wage only covered labor. The builder did not supply materials (mudbrick, reeds, timber) and was typically given barley rations (daily or monthly) during the project. This compensation places builders firmly in the skilled artisan class.

Agricultural Labor Wages

- Law §257: The annual wage for a farmer is set at eight gur of grain per year, or $1,620 in today’s money.

- Law §261 sets a shepherd’s wage at the same rate.

- Law §258 sets a “cowman’s” wage slightly lower, at six gur/year, or $1,215.

To put these annual wages in perspective: 6–8 gur of barley would have been enough to sustain a small family for a year if carefully managed. Lower-skilled laborers were typically paid at a subsistence level. They might accumulate small amounts of silver over time if their employer settled any surplus or bonuses in silver at the end of a season.

Renting Equipment

- Law §271: The price of renting cattle, a wagon, and its driver is set at three pānum (180 liters) of grain per day. This equates to $122.

This is very steep rate. It likely includes feed for the oxen (they eat a lot), the labor of the driver, and the fact that the oxen and wagon (capital assets) undergo wear and tear. Oxen were expensive to buy and maintain. A tenant farmer who didn’t own his own ox team would have to pay this rate to plow fields or transport goods during the peak season, which could eat up a lot of his profit.

Wages for Day Labor

- Law §273: The daily wage of an unskilled laborer is set at six grains of silver ($6.75) during peak agricultural season and five grains of silver (about $5.63) for the off-season.

In modern terms, $6 per day is extremely low. But again, this is a subsistence wage. It would have covered a household’s daily needs when made into bread and beer. Six grains of silver was equal to 10 liters of barley, which can make about 10 loaves of bread.

When a law says “6 grains of silver per day,” it does not mean the laborer was handed tiny flecks of silver every evening. The employer tracked a laborer’s time at the silver rate, but paid them in barley rations each day/week to keep them fed. At the end of the work period, if the laborer had earned more than the value of the rations already given, the balance might be paid in silver. This is why the law specifies the unit of account (silver) even when actual payment was in barley.

Summary of Ancient Prices and Modern Equivalents

| Law | Description | Ancient Babylonian Price | Modern U.S. Dollar Equivalent (Estimated) |

|---|---|---|---|

| §215 | Surgery on a nobleman | 10 shekels | $2,025 |

| §216 | Surgery for muškēnum (commoner class) | 5 shekels | $1,013 |

| §217 | Surgery on a slave | 2 shekels | $405 |

| §221 | Healing broken bone | 5 shekels | $1,013 |

| §198 | Blinding or breaking the bone of a commoner | 1 silver mina | $12,153 |

| §228 | Labor for building a house (per 390 sq ft) | 2 shekels | $405 |

| §257 | Farmer’s and shepherd’s annual wage | 8 gur of barley | $1,620 |

| §271 | Daily rental for wagon, driver, and cattle | 3 pānum of barley | $122 |

| §273 | Daily wage for unskilled labor | 5–6 silver grains | $5.63–$6.75 |

An Alternative Method of Comparing Ancient Babylonian Prices

Using gold as a baseline is informative, but it’s always good to double-check with other methods. We can ask, how much bread did the ancient wage buy, versus a modern wage?

An unskilled Babylonian worker got 10 liters of barley per day (which can make roughly 10 loaves of bread). Laborers worked sun-up to sun-down during peak season; shorter days off-season (on average, 10 hours/day).

The average minimum wage in the United States is about $10/hour (the federal rate is $7.25/hour, but most states mandate higher rates). At 10 hours of work per day, a modern worker can earn $100/day. With an average loaf of bread costing $3.00, that daily wage buys 33.3 loaves of bread.

A modern low-wage worker can afford over 3 times as much bread per day as an unskilled worker in ancient Babylon.

Of course, an apples-to-apples comparison would need to account for taxes, government-provided benefits (cash, food, housing, and healthcare), employer benefits, and other differences in economic organization. In ancient Babylon, 65-80% of people lived on subsistence wages. In the modern U.S., only about 10% of workers are clustered near the bottom of the wage distribution.

Food Purchasing Power Comparison

| Economy | Daily Low-Skilled Wage | Equivalent in Loaves of Bread |

|---|---|---|

| Ancient Babylon | 5–6 grains of silver | 10 loaves |

| Modern U.S. | $100/day | 33.3 loaves |

Conclusion

By using gold as an anchor across time, we preserve some sense of the purchasing power embedded in ancient prices. Of course, this is an estimation tool, not an exact science. But it helps our understanding tremendously. Instead of seeing “5 shekels” as an abstract old number, we can think “about a thousand bucks,” which intuitively tells us, “Ah, that was pretty expensive, maybe a few months’ pay for a laborer.”

Gold does not corrode or perish with time, and neither does the economic logic that something scarce and desired will hold its value through the ages.

Vaulted: Real gold without the excessive fees

Today, we live in a world of fast-moving prices, expanding money supply, and financial systems that feel increasingly abstract. The challenge is the same as it was 3,700 years ago. How do you preserve purchasing power across time?

That’s the problem Vaulted was built to solve.

Vaulted lets you own real, physical gold and silver, stored securely in professional vaults, fully allocated to you. No paper claims, no ETFs. Just modern infrastructure wrapped around the same idea ancient civilizations already understood: hard assets endure.

If history teaches us anything, it’s this: when value matters, people return to real money. Vaulted simply makes that easier.